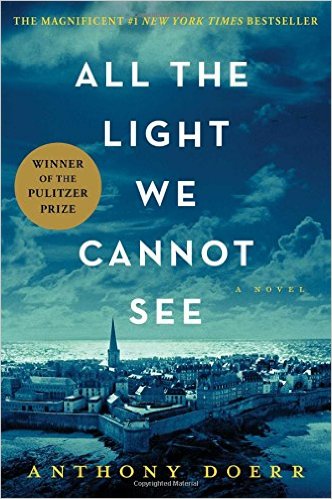

All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

What if you couldn’t see war happening around you, but you could hear it, smell it, taste it, and feel it?

What if everything you believed to be wrong, suddenly became right?

Does morality still exist in wartime?

Can kindness survive?

Anthony Doerr’s All The Light We Cannot See explores these poignant questions and more by telling the parallel stories of Marie-Laure and Werner, a blind French girl and young German soldier, respectively, as each struggles to survive the immense horrors of WWII.

After fleeing war-torn Paris, Marie-Laure and her beloved father find refuge at the seaside home of an allusive great-uncle. Marie-Laure can hear the waves crashing just outside the window, and excitedly awaits the day when her father will bring her to feel the sand beneath her toes. After her father leaves town for what is promised to be a short trip and never returns, however, Marie-Laure must for the first time in her life, navigate the world on her own, and in the meantime, discovers she is harboring a dangerous secret.

While Marie-Laure is confined to the walls of Saint-Malo, Werner’s career as a member of Hitler Youth and later, as a Nazi soldier, takes him from a German orphanage across Europe and eventually, to the home of Marie-Laure’s great uncle. As their two journeys collide, Werner faces the moral dilemma of following his heart or obeying his training, leaving the fate of Marie-Laure – and her secret – in his hands.

A masterfully written tale of perseverance, All The Light We Cannot See will have adolescent and adult readers alike considering questions of morality, loyalty, and love, in a truly powerful way that transcends time and space. Oscillating between the perspectives of Marie-Laure and Werner, All The Light We Cannot See would likely fall between the Middle High to High Classification of text complexity within the YA genre from both quantitative and qualitative standpoints. Similar to Glaus’ description of Glimpse in her article, “Text Complexity and YA Literature,” All The Light We Cannot See presents “Mature issues and themes most likely different from those of the common reader… establish[ing] a higher knowledge demand. Because this text displays a complex narrative structure, mature issues… and shifts in chronology, I place it on the ‘high’ level of qualitative text complexity for structure” (412). Unlike Glimpse, however, All The Light We Cannot See does make use of more traditional text features, perhaps making it a slightly more accessible read. While some historical context about WWII and the political climates of France and Germany in the 1940s may be beneficial, extensive background knowledge is by no means required, and a brief overview would adequately equip students as they prepare to begin the novel.

Furthermore, by including the disparate perspectives of Marie-Laure and Werner, All The Light We Cannot See provides students with an array of possible windows and mirrors in which they can see their experiences and others’ represented (Bishop). Specifically, the novel includes representations of the following, among others: male and female leads; persons with disabilities; oppressors and the oppressed; single-parent families; and orphans. In so doing, this excellent piece of historical fiction sheds light on a myriad of situations with authenticity and accuracy, allowing for a diverse and dynamic reader experience.

In conjunction with the several Essential Questions listed at the beginning of this post, All The Light We Cannot See invites the use of many supplemental texts that also pertain to such issues of morality and humanity in the face of conflict. For instance, educators could incorporate additional historical context to provide students with greater background knowledge about WII. Possible resources include documents about the Hitler Youth Movement and maps of Europe in the 1940s. A specific article, originally published in the March 10, 1907 issues of the Washington Times, that may be of interest when teaching All The Light We Cannot See as a whole class text has recently been made available online. It documents the Eiffel Tower’s early use as a wireless broadcasting system, providing details that would likely enhance readers’ understanding of and appreciation for the novel’s repeated discussion of radios. More contemporary additions could be made possible through the use of poetry (for example, Billy Collins’ The History Teacher, which deals with issues of authority and the ways in which history is presented) as well as a variety of current events articles (Marie-Laure’s escape from Paris and the current Syrian refugee crisis offer ample opportunity for comparison).

All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr would be an excellent choice for a whole class text at Brown Summer High School because it presents students with gripping storylines that would appeal to an array of reader preferences. Whether interested in romance, war, or suspense, the novel is complex in its structure and content yet approachable, and is sure to engender meaningful dialogue within the classroom and beyond it. Though a fairly long text (530 pages, to be exact), the short nature of its chapters seems to expedite the reading process, and thus need not be viewed as a deterrent. First published in 2014, Anthony Doerr’s All The Light We Cannot See has quickly proven an important and effective addition to the YA genre, and is sure to influence developing readers for many years to come.

By: Mia Rotondi

Full publishing citation: Doerr, Anthony. All the Light We Cannot See. New York, NY: Scribner, 2017. Print.